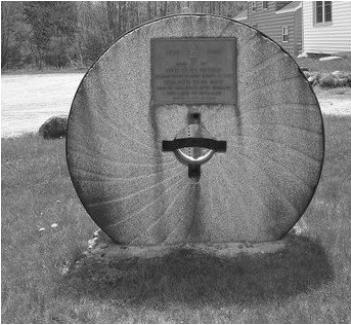

This millstone marks the site of the Pine Tree Riot where Quimby's Inn once stood.

It is located on Rte. 114, South John Stark Byway near the Avon store on Eastman Hill.

(Photo by Sherry Hadley Burdick)

Site of Pine Tree Tavern

where took place April 14, 1772

THE PINE TREE RIOT

one of the first acts against

the laws of England

Information about this event was obtained from William Little's History of Weare,

New Hampshire

1735-1888 (Lowell, MA: published by the town, 1888), 185-191.

Information about the masting trade came from New Hampshire Crosscurrents in Its Development

by Nancy Coffey Heffernan and Ann Page Stecker

(Hanover and London: University Press of New England,

1996), 32-36.

The Pine Tree Riot occurred at Quimby's Inn in South Weare on April 14, 1772. The event that spring morning was precipitated by men from Weare and surrounding towns illegally cutting white pine trees reserved for masts for the Royal Navy. But there was much more to it. "The story of the English need for ship's masts, ship's timber, and naval stores and young New Hampshire's ability to provide these commodities is a tale of market dynamics, imperial politics, ecological shortsightedness, and crafty survival tactics…." 1 In short, timber was to the world at that time what oil is to the world today--a finite resource for which nations competed.

When the first shipment of masts from Portsmouth to England occurred, in 1634, England had already suffered deforestation. In order to dominate the high seas, new sources of abundant timber for shipbuilding were needed. "No ships, after all, could catch the wind without as many as twenty-three masts, yards, and spars varying in length and diameter from the bulky mainmast to its subordinate parts." 2 Although New Hampshire's white pine was not as hard as Europe's, its height and diameter were superior. It also weighed less and retained resin longer, giving the ships a sea life as long as two decades.

When granting lands in America in 1690, King William prohibited the cutting of white pine over two feet in diameter. In 1722, under the reign of George I, parliament passed a law that reduced the diameter to one foot, required a license to cut white pine, and established fines for infractions.

This law was basically ignored until John Wentworth became governor in 1767. Appointed Surveyor of the King's Woods, he recognized the revenue potential and appointed deputies to carry out the law. He conducted his own inspections of mill yards in the Piscataquog valley by having a servant drive him around in his coach.

Before settlers could clear the land or build cabins, barns, or meetinghouses, the king's sanction, a broad arrow mark, was required on trees reserved for the Royal Navy. The deputies charged them a "good, round sum" to mark the trees and for the license required to cut the rest. No wonder the law became unpopular. The consequences involved arrest and fines. Contraband white pine already sawed into logs could be seized and a large settlement required; if not paid, authorities sold them at public auction.

In the winter of 1771-72, a deputy Surveyor of the King's Woods found and marked for seizure 270 mast-worthy logs at Clement's mill in Oil Mill (now called Riverdale), in South Weare. He fined the log-cutters from Weare and those from nearby towns where illegal logs were also found. Men from other towns paid the fines, but those from Weare refused. Consequently, the Weare men were labeled "notorious offenders."

The county sheriff, Benjamin Whiting, Esq., of Hollis, and his deputy, John Quigley, Esq., of Francestown were charged with delivering warrants and making arrests in the king's name. On April 13, 1772, they galloped into Weare and found major offender Ebenezer Mudgett, who promised to pay his fine the next day. The officials then retired to nearby Quimby's Inn for an overnight stay.

News that they had come for Mudgett flew through town, and a plan was hatched. The following morning more than twenty men with blackened faces and switches in hand rushed into Whiting's room led by Mudgett:

Whiting seized his pistols and would have shot some of them, but they caught him, took away his small guns, held him by his arms and legs up from the floor, his face down, two men on each side, and with their rods beat him to their hearts' content. They crossed out the account against them of all logs cut, drawn and forfeited, on his bare back….They made him wish he had never heard of pine trees fit for masting the royal navy. Whiting said: "They almost killed me."3

As for Deputy Quigley, the Weare men wrested the floorboards from the room above his and proceeded to beat him with long poles. Nor did the officials' horses escape the men's wrath. They cropped the animals' ears and sheared their manes and tails. To "jeers, jokes and shouts ringing in their ears" the sheriff and deputy rode toward Goffstown and Mast Road, named for the logs that were moved overland to the sea and off to England for the king's ships.

The Weare men were ultimately arraigned and paid a light fine, but their rebellion against the crown, which preceded the Boston Tea Party (1773), helped set the stage for the Revolution. People in New Hampshire were probably more offended by the pine tree law than the Sugar Act of 1764; the Stamp Act (a rebellion that took place in Portsmouth, NH, in 1765); and the duty on tea, passed in 1773, which precipitated the Boston Tea Party. According to Weare's 1888 history, "The only reason why the 'Rebellion' at Portsmouth and the 'Boston tea party' are better known than our Pine Tree Riot is because they have had better historians." 4

~~~

About 150 years after the Pine Tree Riot, sawmills still dotted Weare's landscape.

(from Weare Historical Society archives)

1 Nancy Coffey Heffernan and Ann Page Stecker,

New Hampshire Crosscurrents in Its Development(Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 1996), 32.

2 Heffeman and Stecker, 33.

3 William Little, History of Weare, New Hampshire

1735-1888, (Lowell, MA: published by the town, printed by S.W. Huse & Co., 1888), 189.

4 Little, 191.